By Alfie Fuller – Think Research

Aviation plays a critical role in global connectivity, yet its environmental footprint is undeniable. The industry accounts for approximately 2 to 3% of global CO2 emissions, alongside non-CO2 emissions and a high dependency on fossil fuels, all of which have a negative climate impact. In response, sustainable aviation practices are becoming ever-more prevalent to increase the industry's longevity. Throughout the sector ambitious environmental targets have been set, including:

- The UK Civil Aviation Authority aims for net zero aviation by 2050, with a 10% sustainable aviation fuel mix by 2030.

- The European Union RefuelEU initiative sets requirements for aviation fuel suppliers to increase the share of SAF blended into conventional aviation fuels supplied to EU airports to 70% by 2050[1].

- ICAO’s long-term global aspirational goal (LTAG) targets net zero carbon emissions from international aviation by 2050[2].

Achieving these environmental sustainability goals requires significant improvement in airspace design and management as well as sector wide investment in new aircraft and in the infrastructure to produce and deliver alternative fuels. Such substantial changes and investment are reliant on strong collaboration between industry players, governments and regulators.

While environmental sustainability is a key focus, sustainability is an all-encompassing term for the ability to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In effect, this means using resources efficiently, reducing waste and emissions, promoting social equity and supporting economic viability while preserving ecosystems and biodiversity. Without tackling the large-scale change required for longer term environmental sustainability, plenty can be done in today’s airspace environment to create a sustainable future for aviation. The challenge lies in effectively balancing environmental, social and economic factors while continuing to meet safety standards.

This article focuses on how we can ensure social sustainability when considering changes to the airspace environment. Highlighting the importance of accepting the need for balance while underscoring the inherent difficulty of doing so effectively.

Balancing environmental and community needs - the emerging trade-off model

Safety remains the highest priority in aviation, governed by stringent regulations. As a result, when evaluating potential changes to the airspace environment, it is essential to clearly prioritise safety as a fundamental principle. However, beyond safety, balancing environmental impacts, economic sustainability and community well-being presents an increasing challenge.

Pollutants, such as CO2, nitrous oxides, sulphur oxides and particulate matter, as well as certain types of contrails, are key to reduce for a clean atmosphere and stable climate for future generations. In the near term, we can contribute to this by optimising aircraft trajectories through reduced holding, continuous climb and descent operations, optimising altitudes and speeds and considering meteorological factors. But ultimately, the further an aircraft flies, the more of these emissions it generates. At low altitudes surrounding airports, there are additional challenges in balancing carbon emissions with noise, which can have disproportionate effects on local communities and ecosystems if not managed in a sustainable way.

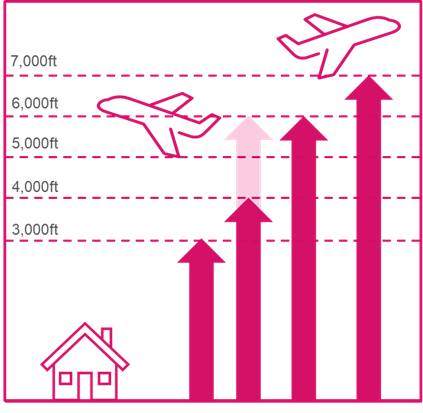

Sustainable airspace management requires balancing competing priorities in a way that is both environmentally responsible and socially equitable. Trade-offs are inevitability required to enable sustainable airspace use. A growing trend in airspace management is the formalisation of trade-offs between noise and carbon emissions. Many air navigation service providers (ANSPs) and regulators are adopting altitude thresholds to determine when noise impact should take precedence over carbon emissions and vice versa. Typically, noise concerns dominate at lower altitudes, with carbon emission reduction becoming a priority at higher altitudes. However, the practices differ globally with a wide range in the thresholds set and approaches adopted, for example some countries:

- Set thresholds based on noise levels associated with high levels of reported annoyance within the population.

- Set thresholds considering the lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) of noise on health.

- Adopt a multi-tiered strategy, categorising altitudes into noise-priority zones (low altitude), balance zones and operational efficiency priority zones (higher altitudes).

The figure below visualises four practices seen across countries. The dark pink arrows indicate the altitude band where noise reduction is prioritised within airspace changes. The ceiling altitudes - after which noise is determined to no longer be a factor - range from 3,000ft to 7,000ft. The light pink arrow indicates a a multi-tiered strategy, the altitude band where both noise and carbon emissions are balanced sitting between 4000ft and 6000ft.

While this structured approach simplifies decision-making, it does not eliminate the complexities of community impact. Additionally, the variation in approaches can make it difficult for stakeholders to understand and lead to gaps in accountability or a lack of tailoring to specific local circumstances. Establishing trade-off thresholds does not, on its own, provide clear direction on how to balance the complexities of noise and emissions.

The role of social sustainability in airspace management

This is where the need for social sustainability enters the equation. Aviation must ensure its long-term presence does not come at the cost of community well-being. When considering changes to lower level airspace, it is particularly important to embed such social sustainability into the design, decision-making process and community consultation process.

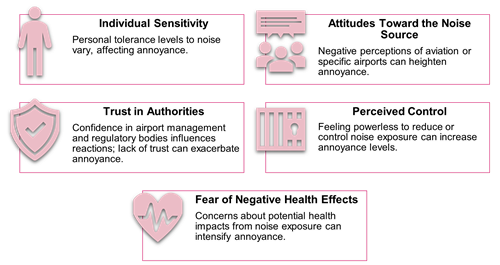

For example, simply mapping the shortest routes would reduce carbon emissions but may concentrate the noise impacts in specific areas, disproportionately affecting some communities and wildlife. This requires careful engagement with communities to ensure that decisions account for the specific characteristics of noise-sensitive locations, such as schools, hospitals and areas designated for quiet recreation, where even small increases in noise can have disproportionate effects. There is also a need to consider communities not previously affected by aircraft noise and strategies for providing respite periods for those experiencing frequent overflights - although this in turn can lead to an increase in the total number of people affected by aviation impacts. Such decisions therefore require clear principles regarding the distribution of benefits and burdens. These principles should provide decision makers with clarity on e.g. whether to prioritise reducing the total number of people impacted or to share the burdens evenly. Additionally, non-acoustic factors should not be forgotten, as shown in Figure 1, these factors can have a significant influence over the community acceptance for changes to the airspace environment[3].

Building community truth through transparent data sharing

Beyond balancing the immediate impacts, transparency and trust-building are vital. The aviation industry must clearly communicate the rationale for airspace changes, assess the options that exist for changes to the airspace environment and acknowledge that not all parties will benefit equally. By openly discussing trade-offs (with or without a pre-determined trade-off point) and engaging stakeholders early, regulators, airports and ANSPs can foster greater public confidence in the decision-making process.

Aviation emission modelling tools can be used to help communicate with stakeholders about airspace changes and build stakeholder trust through the provision of data. These tools allow for detailed modelling of climate change effects, noise impacts and air quality effects and are critical in conducting environmental impact assessments and informing airspace changes. However, their effectiveness depends on the effectiveness of the analysis approach. For example, assumptions made in the modelling significantly influence the results, yet too often, the relevant stakeholders are not engaged in developing and confirming these assumptions. Similarly, how modelling outputs are presented will influence perceptions and acceptance. Selectively framing data by adjusting baseline conditions, emphasising certain metrics or altering modelling assumptions can skew public perception. For instance, failing to account for ground attenuation in noise modelling can lead to incorrectly estimating real-world impacts. Whether intentional or accidental, misrepresentation can erode trust in the industry, reinforcing public scepticism rather than fostering collaboration.

These examples underscore the need for stakeholders to be engaged openly and transparently when undertaking changes to the airspace environment. To help to build community confidence, aviation stakeholders can:

- Make data and methodologies publicly accessible in an understandable format.

- Clearly explain modelling assumptions and their limitations.

- Engage independent assessors to validate findings and ensure credibility.

Though not all parties may benefit, transparency aids stakeholders in understanding how changes serve the greater good. Establishing well-defined objectives for changes before implementation is a safety net to ensure effective commitment to social sustainability. This includes setting clear objectives, defining assessment methods and measures and maintaining a consistent methodology.

Economic sustainability and future challenges

While environmental and social sustainability are crucial, economic resilience remains a cornerstone of aviation’s long-term viability and cannot be forgotten. The transition to sustainable aviation requires substantial investment in infrastructure, technology and operational improvements. This includes large investments in green infrastructure and modernised ATM system. In fact, a recent report ‘Destination 2050- A route to net zero European aviation’[4] estimates that decarbonising the aviation sector will necessitate total expenditures of €2.4 trillion, marking a 27% increase from previous estimates. This rise is primarily attributed to escalating energy costs and the need for sustainable infrastructure development. Collaboration between regulators, governments, manufacturers and operators is hence essential to driving the adoption of greener solutions. Effective policy support is required to enable the transition to sustainable aviation, ensuring that industry efforts align with broader societal and environmental objectives.

Even as we move beyond traditional aircraft and begin to use future aviation fuels, sustainability challenges will continue to exist with an increasing focus on social sustainability. The rise of future flight technologies, including electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft and drones, is likely to introduce new complexities[5]. These operations will take place at lower altitudes, heightening the importance of considering social impacts such as visual blight and non-acoustic noise factors. To successfully integrate these technologies, we will need strong regulatory frameworks and proactive engagement with communities to address and mitigate potential negative effects.

As aviation moves toward a net zero future, environmental sustainability alone is not enough. Social sustainability - ensuring that airspace management decisions are equitable, transparent and responsive to community needs - must be embedded in industry practices. The industry must engage openly with affected communities. Transparent communication, data sharing and a commitment to social responsibility will be critical in shaping a sustainable future for aviation.

.jpg)

.png)